Phalanstery: the early Soviet idea of collective living

The “phalanstery” was a concept for a new type of housing, also known as the communal house.

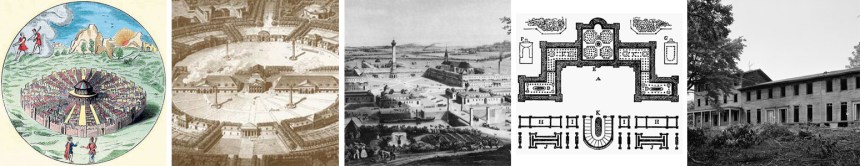

It emerged in Russia in the early twentieth century and was mentioned in Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s book A Vital Question. The term itself originates from the nineteenth century, appearing in the works of Charles Fourier (François Marie Charles Fourier).

Living in a phalanstery offered people the opportunity to concentrate on productive work while increasing efficiency through collaboration with fellow residents to promote economic growth.

The idea was to optimise daily life in order to encourage participation in collective labour.

It represented a social utopia of collectivism, later translated into physical community housing developments during the early Soviet period.

Excellent — the content is strong and historically interesting. Below is a polished version in clear, natural British English, keeping your academic tone but making it flow smoothly for modern readers:

The Concept of the Community House

The idea of the community house was based on the concentration of all essential infrastructure within a single building or complex. As Le Corbusier famously stated, “The house is a machine for living in.”

The organisation of communal housing enabled residents to meet all of their everyday needs — work, study, sport, and social life — without leaving the complex. At its core, the concept aimed to cluster communities to reduce costs and increase productivity.

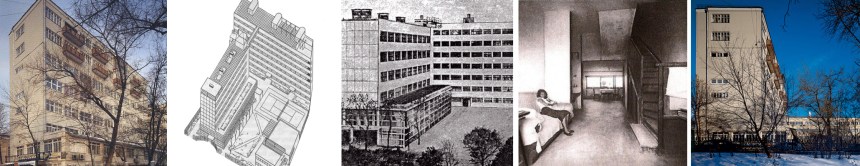

A typical Soviet phalanstery consisted of a single building with minimalist flats and large communal zones, designed to encourage active participation in collective life. According to the concept, an individual’s apartment was to be used only for basic functions such as sleeping and rest. The interiors were furnished simply and functionally — with built-in cupboards, very small kitchens, and modular furniture.

Several standardized types of so-called “living cells” were designed for use across different residential buildings. The public areas were intended to draw residents into shared activities, and the ideology even proposed replacing family ties with communal relationships as part of building a new social order.

The service infrastructure — including a canteen, kindergarten, laundry, library, and clubs — formed an integral part of the complex. As a result, residents did not need to worry about everyday domestic services and could devote more time to collective pursuits.

Case studies illustrating these ideas are shown in the examples below.

The House of the People’s Commissariat of Finance, designed by architect Moisei Ginzburg, is one of the most celebrated examples of Constructivist architecture and is recognised today as a site of world heritage significance.

The House of Comradeship of Representative Construction is one of the most renowned examples of its type. The architects who designed it also lived there, turning the building into a living laboratory for experimenting with the design of “living cells” — the modular residential units characteristic of early Soviet communal housing.

The House for Students is noted for having some of the longest corridors in residential architecture, connecting all living quarters like internal streets. After a period of abandonment, the building has been fully renovated in recent years and now functions as a student hostel, complete with all the necessary modern facilities and infrastructure.

The House on the Embankment stands somewhat apart from the other examples because of its different function, yet it follows the same organizational principles. Built to accommodate high-ranking government officials, the building is located in the city centre, allowing residents to travel quickly between home and work.

The further development of the phalanstery concept led to a new variation of communal housing.

In the mid-twentieth century, buildings were constructed for specific professional groups, such as the House of Professors, House of Architects, House of Composers, House of Painters, and House of Writers, among others.

The goal was to enhance the productivity of living, working, and creative processes. Residents were grouped according to their profession, forming a kind of cluster economy within the housing complex. Economic studies suggest that when people live and collaborate within professional clusters, they tend to generate higher levels of productivity and financial output.

The idea of the phalanstery was, in all likelihood, too radical and too heavily imposed from above, which prevented this type of housing from becoming widely adopted. Nevertheless, clustering occurs naturally: in some buildings, residents still belong to particular professional communities, and in Moscow, for example, there is a district with a high concentration of architectural firms.

Today, thanks to the rise of digital communication, a kind of virtual community clustering has emerged through social media, allowing people to collaborate and share professional activities while being physically distant. At the same time, the principle of clustering to enhance productivity has been actively adopted in business environments, where teamwork and shared space are recognised as key drivers of efficiency and innovation.